Excellent review – how Lost influenced modern media culture

LOST, Ten Years Later: A Defense

By Jack Butler May 31, 2020

It wasn’t a perfect show, but today’s critics give it short shrift.

A man in a suit opens his eyes in the middle of a jungle. He doesn’t know how he got there. He is hurt but not seriously injured, though definitely disoriented. Out of nowhere, a yellow Labrador pops out of the dense foliage, then disappears back into it. The man gets up. He runs through the trees around him, reaching a beach. He looks around, as noises of creaking machinery and human anguish fill his ears. Before him are the remains of a plane crash. He was one of the passengers.

These were the opening moments of LOST, which premiered on ABC on September 22, 2004. Created by J. J. Abrams, Jeffrey Lieber, and Damen (sic) Lindelof, LOST was — to vastly simplify things — the story of the survivors of a plane crash that brought them to a mysterious island of far greater importance than it first appears. From its very first moments, it was an arresting, ambitious, and mysterious program, which had production values and a cast (and a budget) that more resembled those of a Hollywood movie than a network TV show. Many fans hooked by that first episode quickly became obsessed with this enigmatic, ensemble-driven drama. Fans like me. I watched every episode, browsed fan forums and Lostpedia obsessively, listened to the discussion podcast that showrunners Carlton Cuse and Lindelof hosted, and discussed LOST with other fans in the real world. For much of its run, LOST combined the devotion typically engendered only by cult phenomena with a strikingly mainstream appeal: At around 20 million viewers an episode at its peak ratings, it was one of the most popular shows on television.

Yet today, ten years since the last episode of LOST aired, the show is remembered in controversy. For some, the mystery and drama that drove the show from its first moments led ultimately to disappointment by its end. Writing for Salon in 2013, for example, Daniel D’Addario labeled “The End,” LOST’s final episode, one of the worst finales ever, a “culmination of a show whose twists and turns didn’t always seem to be undertaken by people who knew what they were doing.” Others complain that few of the show’s many mysteries were answered, or that the entire show was a waste of time, a con.

It is certainly true that some of LOST was generated ad hoc. But the trumped-up version of that criticism both is incorrect and ignores how stories are constructed. It is also true that some of the show’s mysteries received nonexistent or incomplete answers, though this criticism, too, is overstated. And even to the extent that these criticisms are true, they do not detract from the fact that LOST was an incredibly well-made show that inspired much of the television that came after it and set the template for modern television fandom.

The essential thrust of LOST is this: The survivors of the plane crash whose aftermath opens the show come to explore, over the course of its six seasons, both the mysteries of the island where they have crashed and the secrets their fellow castaways are hiding from one another. They learn, among other things, that they are not alone on the island, and that it is a place of immense significance. By the end of the show, it has become clear the island was, from the beginning, inextricably linked with the fates of the survivors themselves. They end up an essential part of an epic struggle over the island of much greater importance than their own lives, yet one that also provides their lives meaning. All of them were “looking for something they couldn’t find” outside of the island.

LOST is frequently criticized for being aimless, but the creators knew some long-term aspects of the story from the beginning. Before the series began, its creators put together a “bible” sketching out the show’s mythology in broad strokes. This does not explain the entire series. But it did stipulate certain elements that the show extrapolated later from only vague hints early on, such as the island’s ancient history, and the former presence on it of a hidden scientific community investigating its mysteries. Other elements were also present from the start, if, again, only in broader strokes. Abrams has said that a season-one invocation of backgammon, an ancient, chess-like game with “two sides, one light, one dark,” as described in the show, was intended as a symbolic foreshadowing that LOST’s characters would eventually become part of a struggle embodied by two singular entities, which did indeed come to pass. The showrunners knew early on how long the show would go, stating in interviews as early as 2006, less than halfway through its eventual run, that they hoped for 5 to 6 seasons.

Some of what the creators hoped for in LOST they simply could not do. One reason was its sheer popularity. In its first two seasons, LOST was one of the most-watched shows on television, helping to revive ABC’s reputation. Network brass would try to keep that going for as long as they could, forcing the showrunners to strike a tricky balance between keeping the network happy and satisfying their creative vision. As Lindelof said in a 2006 interview, “If we told them we could only do the show if we ended it after 100 episodes, they never would’ve agreed to it. And who could blame them?” LOST fans — and detractors — can see this tension most clearly during the third season, much of which is aimless in a way that lives down to criticism. But it also comes to reflect the finality the writers eventually procured from the network concerning how long the show would go, drawing to an exciting and propulsive climax. Even so, this forward momentum eventually confronted the television-wide Writers’ Guild strike of 2007–08, an exogenous event that resulted in a shortened fourth season. To the end, external factors inhibited the show. It seems unfair to knock a show excessively for such things.

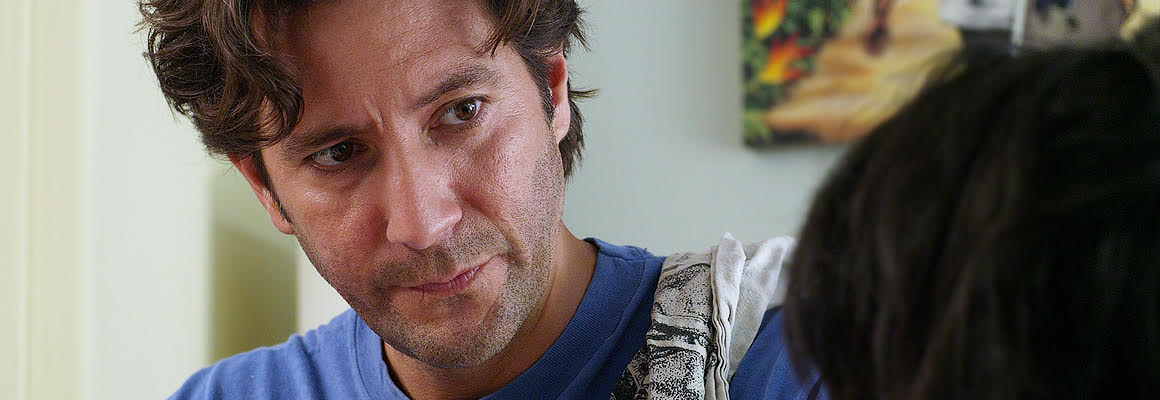

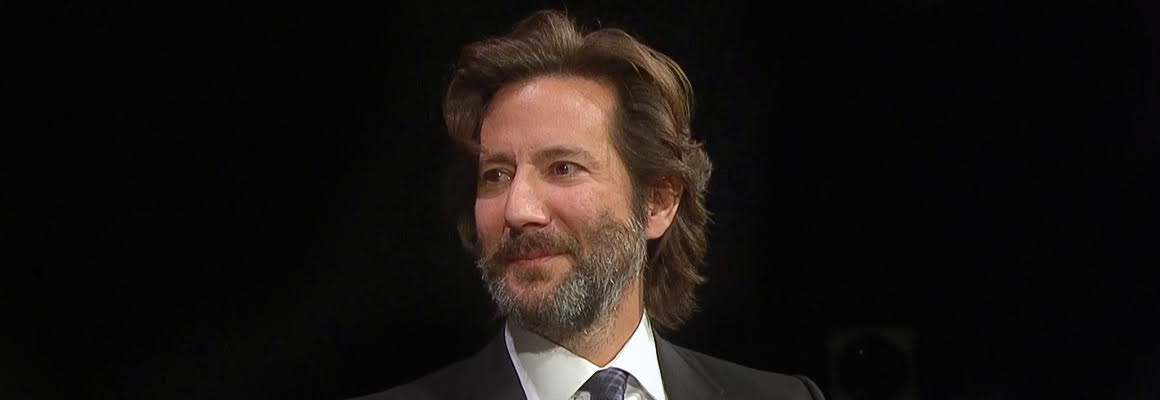

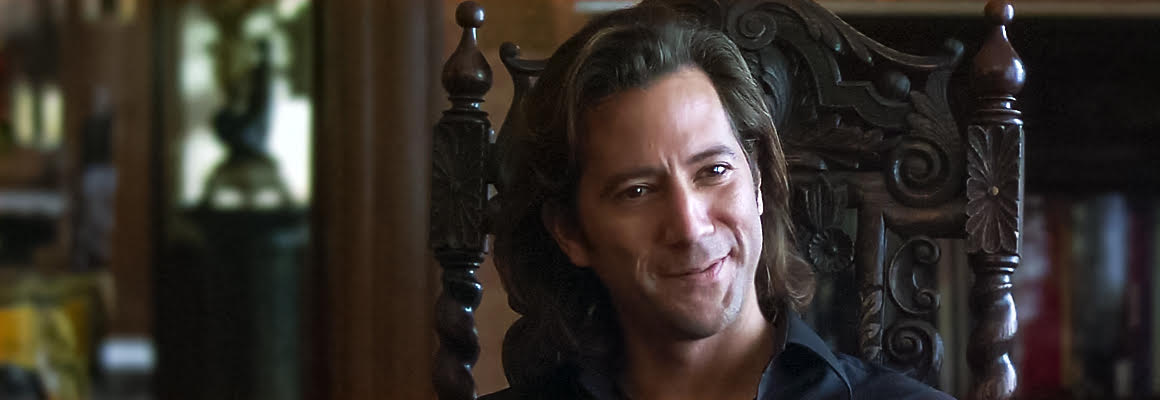

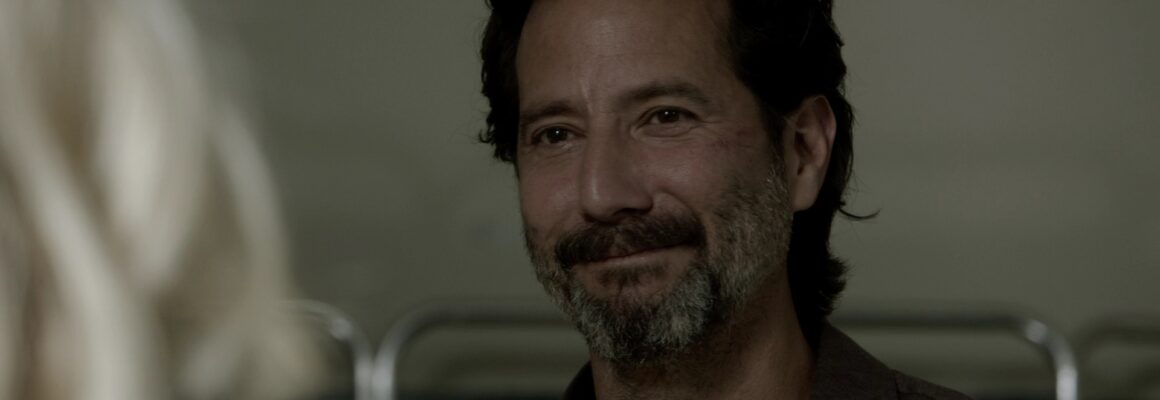

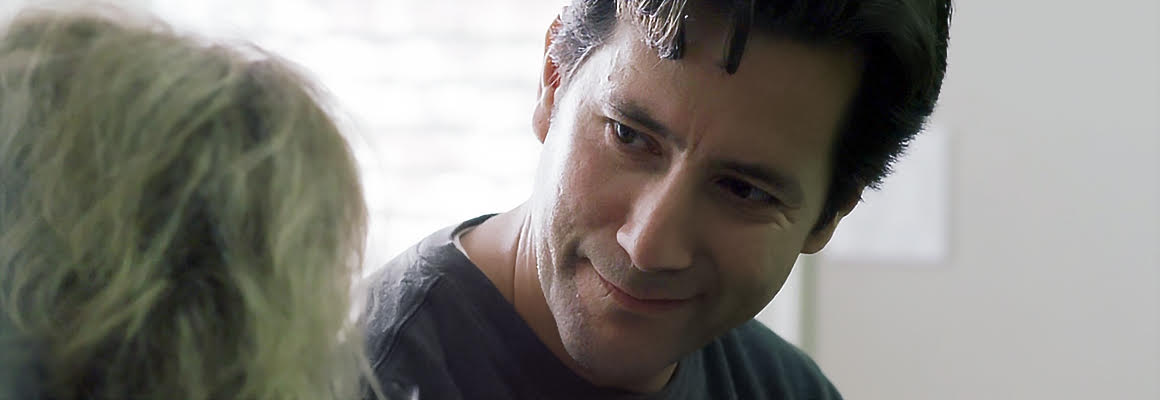

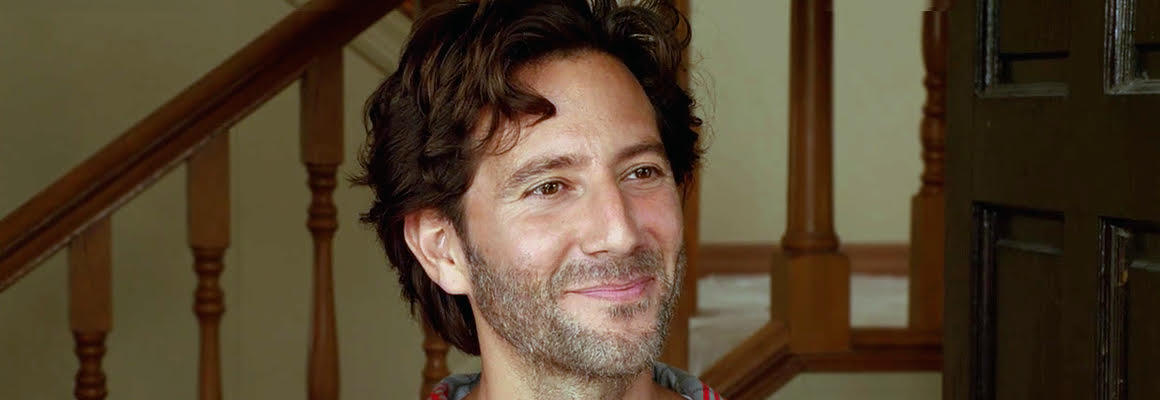

It is more fair to knock it for what it did make up along the way. But even some of the things that were improvised made the show better. The character of Ben Linus (Michael Emerson) was originally written as a bit role but expanded as Emerson made the role his own, lasting until the show’s very end. Ditto the role of Desmond Hume (Henry Ian Cusick), who became one of the most important characters in the series. Likewise, the famous “Smoke Monster,” a malevolent, literally nebulous force that first appears in the very first episode, was originally planned to be a kind of mechanical creation; instead, it developed into an evil entity at the heart of the island’s significance. That some of these developments occurred over the course of LOST is not in itself a strike against them, as some helped the show become better than it otherwise might have been.

Another line of criticism is that the real defect of the make-it-up approach was to indulge the writers’ tendency to create more mysteries than they could solve. LOST was driven, to a considerable extent, by the pervasive aura of mystery and secrecy surrounding not just the island but also the show’s characters. Such mysteries made it fun for fans like me to speculate. They were also an effective way to keep the show going. Despite what lazier critics claim, many of the show’s biggest mysteries actually were answered; many of the answers are out there, for those who want them. Not all the answers were satisfactory to everyone, to be sure, but a boringly expository climax would have deprived LOST of its mysterious aura that remained to the show’s very end, leaving alive the possibility of interpretation and speculation to fans and critics alike on some of its questions to this very day.

But these criticisms miss the show’s true mark of greatness. LOST was great not because it simply had mysteries. It was great because it tied these mysteries into its characters, the true heart of the show, as embodied by one of the most impressive casts ever to appear on television. The Verge’s Jay Peters writes that the point of the show’s finale was to “deliberately show that the real journey, and I mean this with no irony, was the friends the characters made along the way — and maybe that’s what the journeys of our real lives are, too.” Cheesy as this sounds, it’s true. The show, at its best, dealt expertly in universal themes of faith, doubt, redemption, sacrifice, friendship, love, death, rebirth, good, evil, guilt, and sin. All these years later, LOST may be most famous for some of its mysteries. But it deserves to be remembered more for its striking moments between characters who, after six seasons on the screen, became fully realized portraits of humanity in extremis.

This is why, despite the naysayers, LOST became an indelible influence on the television landscape. This was evident almost immediately, with a host of series that premiered just after LOST trying to imitate its sophisticated characterizations and mystery-driven formula. LOST also set the modern template for compulsive fan investigation, beyond mere engagement. LOST fans existed as a community dedicated to probing its mysteries, a process facilitated by technology that was refined or even outright invented — Twitter, Facebook — during the show’s run. All this helped make LOST one of the first and most important TV shows of television’s new “Golden Age.”

LOST is not a perfect show. Shows that rely heavily on mystery are not as rewatchable, as at least some of the joy of watching can come from seeing enigmas appear and unfold for the first time. That also makes an appreciation such as this perhaps unhelpfully subjective; maybe, all these years later, people who were not originally on the show’s bandwagon have no interest in discussing it further. LOST started with broad, mainstream appeal, but maybe now its defense is left to a niche cult of once-obsessed fans like me, who have been with it the moment we saw a well-dressed man first open his eyes in the jungle. If so, that’s okay. We enjoyed it, and that’s good enough.

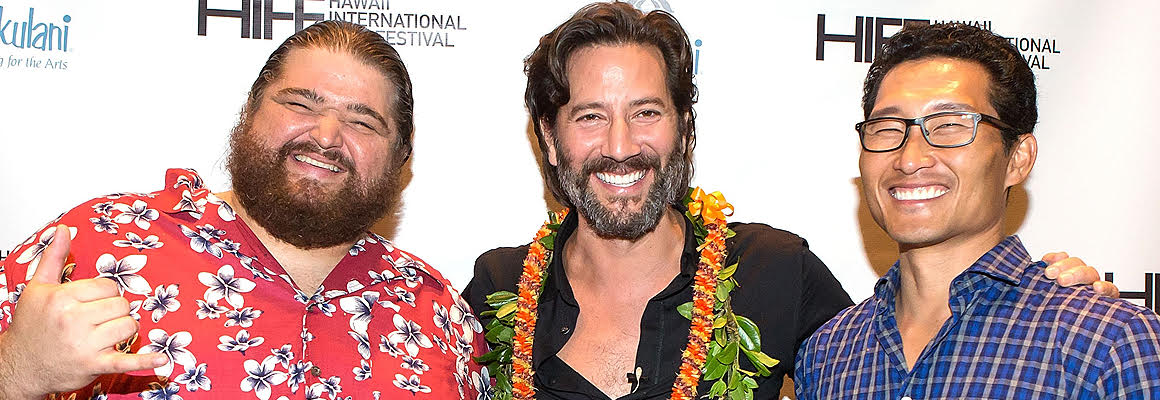

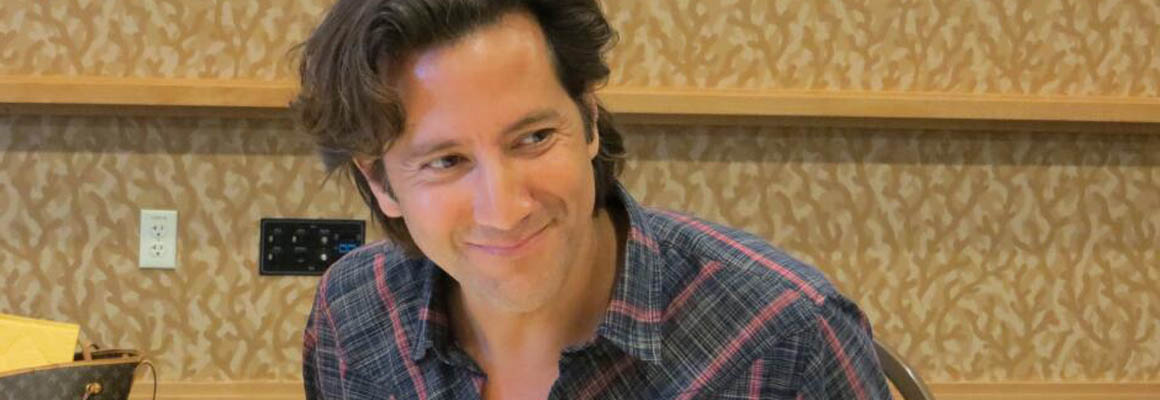

![[1198657408]a MacGyver](https://www.cusickgallery.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/1198657408a-MacGyver-e1627604023448-1160x400.jpg)

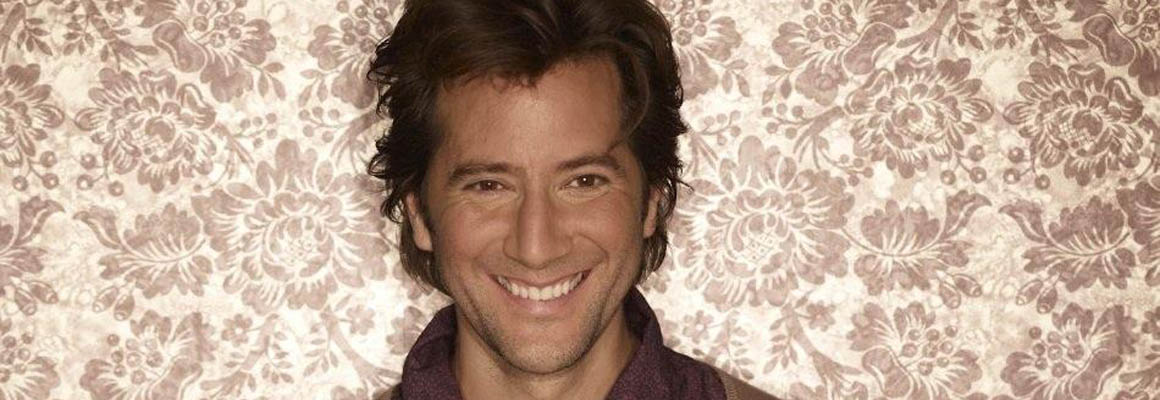

Awaken Film

Awaken Film Henry Ian Cusick – Facebook

Henry Ian Cusick – Facebook Henry Ian Cusick – Vimeo

Henry Ian Cusick – Vimeo Henry Ian Cusick – YouTube

Henry Ian Cusick – YouTube Henry Ian Cusick Official Site

Henry Ian Cusick Official Site Henry Ian Cusick SoundCloud

Henry Ian Cusick SoundCloud Henry Joe Productions

Henry Joe Productions Birthday Edition

Birthday Edition 1 Million Followers

1 Million Followers 10.0 Earthquake

10.0 Earthquake After the Rain

After the Rain Awaken

Awaken Carla

Carla Chimera

Chimera Darwin's Darkest Hour

Darwin's Darkest Hour Dead Like Me:Life After Death

Dead Like Me:Life After Death dress (directoral debut)

dress (directoral debut) Fluxx

Fluxx Frank vs. God

Frank vs. God Hae Hawai'i

Hae Hawai'i Half Light

Half Light Hitman

Hitman Jamojaya

Jamojaya Just Let Go

Just Let Go Not Another Happy Ending

Not Another Happy Ending Pali Road

Pali Road Perfect Romance – Lifetime

Perfect Romance – Lifetime Rememory

Rememory The Girl on the Train

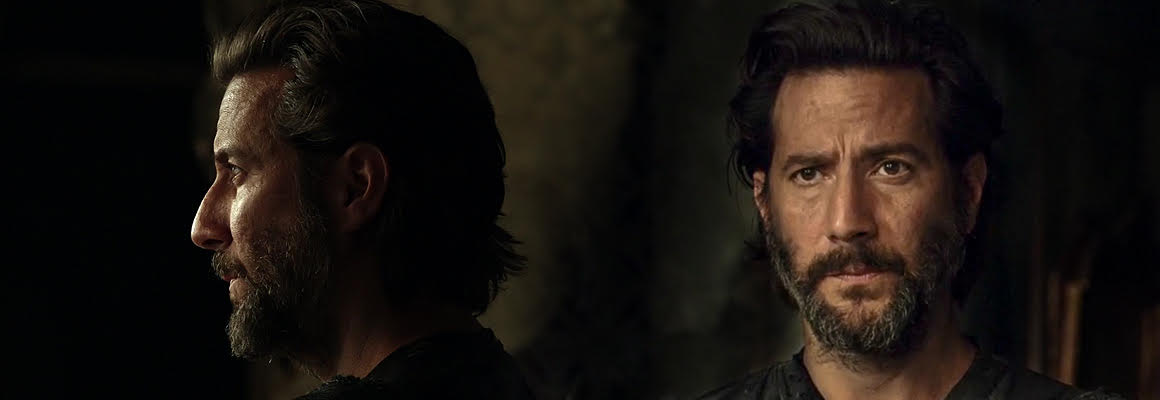

The Girl on the Train The Gospel of John

The Gospel of John The Wind & The Reckoning

The Wind & The Reckoning Visible

Visible Theatre Gallery

Theatre Gallery Adventure Inc.

Adventure Inc. Casualty

Casualty Happiness

Happiness Midsomer Murders

Midsomer Murders Murder Rooms

Murder Rooms Taggart

Taggart The Book Group

The Book Group Two Thousand Acres of Sky

Two Thousand Acres of Sky Waking the Dead

Waking the Dead 24 – Fox

24 – Fox 911: Lone Star

911: Lone Star Big Sky – ABC

Big Sky – ABC Body of Proof – ABC

Body of Proof – ABC CSI: Las Vegas – CBS

CSI: Las Vegas – CBS Fringe – Fox

Fringe – Fox Hawaii Five-O – CBS

Hawaii Five-O – CBS Inhumans – ABC

Inhumans – ABC Law and Order: SVU – NBC

Law and Order: SVU – NBC Lost – ABC

Lost – ABC NCIS: Hawai'i – CBS

NCIS: Hawai'i – CBS Scandal – ABC

Scandal – ABC The 100 – The CW

The 100 – The CW The Mentalist – CBS

The Mentalist – CBS The Passage – Fox

The Passage – Fox HTY – The HI Way Series

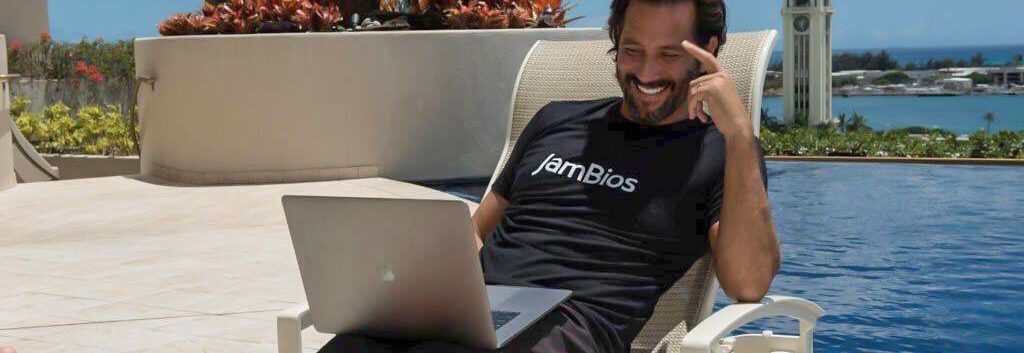

HTY – The HI Way Series JamBios

JamBios Nestor Carbonell Central

Nestor Carbonell Central Petition – Carlton Cuse – Please Make A Show For Team Caliente (Henry Ian Cusick and Nestor Carbonell)

Petition – Carlton Cuse – Please Make A Show For Team Caliente (Henry Ian Cusick and Nestor Carbonell) Cusick On Screen – Instagram

Cusick On Screen – Instagram CusickChick's Tumblr

CusickChick's Tumblr Henry Ian Cusick – IMDb

Henry Ian Cusick – IMDb Shannon's Tumblr

Shannon's Tumblr Yatanis Tumblr

Yatanis Tumblr CusickGallery Facebook

CusickGallery Facebook CusickGallery Instagram

CusickGallery Instagram CusickGallery Pinterest

CusickGallery Pinterest CusickGallery Tumblr

CusickGallery Tumblr CusickGallery Twitter

CusickGallery Twitter CusickGallery YouTube

CusickGallery YouTube Des & Pen Fanpop spot

Des & Pen Fanpop spot Desmond Hume Fanpop spot

Desmond Hume Fanpop spot FanForum – Henry Ian Cusick

FanForum – Henry Ian Cusick FanForum – Marcus Kane

FanForum – Marcus Kane HIC Fanpop spot

HIC Fanpop spot Kane & Abby Fanpop site

Kane & Abby Fanpop site Lost Screencaps site

Lost Screencaps site