The Uniquely Miraculous Desmond David Hume

Really fantastic write-up regarding our Desmond.

Thanks to Mambina for posting the link…and thanks to Pearson Moore for the wonderful tribute!!

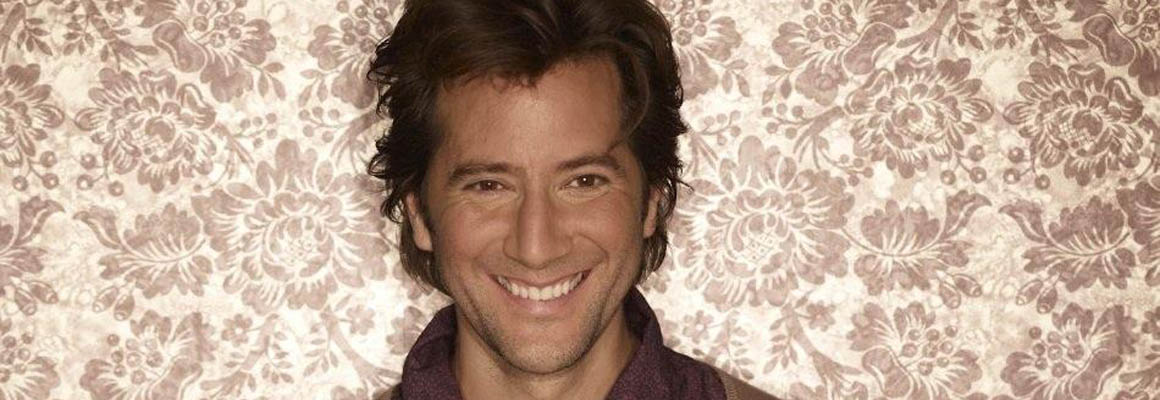

Uniquely Miraculous: The Cultural Triumph of Desmond David Hume in Lost by Pearson Moore

Posted by DarkUFO at 10/09/2010 11:48:00 PM

He was the focus of the greatest single hour of LOST.

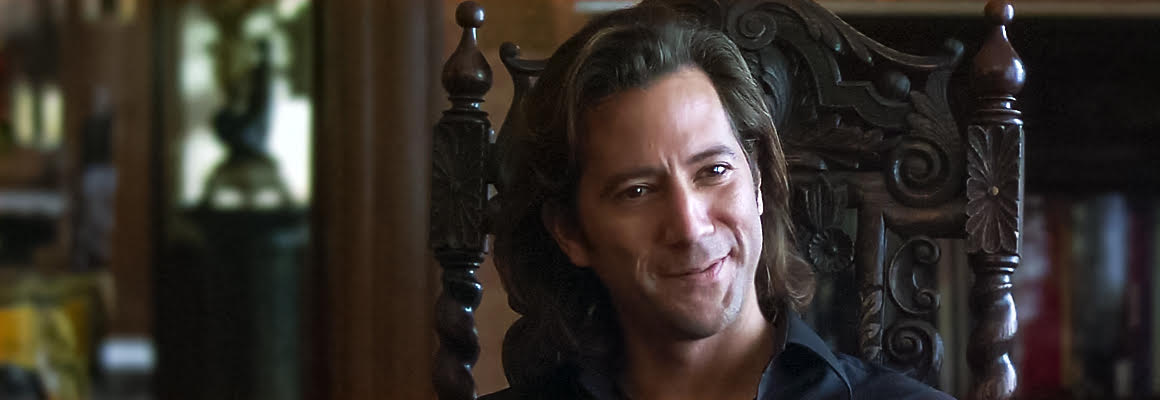

His countenance was the most expressive of any to have occupied the small screen in six years, for he was alone in being asked to perform deeds beyond the capacities of mortal men.

Yet he failed in every occupation he attempted. He backed out of relationships, after six years with Ruth, after several years with Penny Widmore. He was not religious, and he failed as a monk. He designed sets for the Royal Shakespeare Company, and was let go. He tried the life of a soldier, but couldn’t follow orders; after several months in military prison, he was dishonourably discharged from the Royal Scots Regiment. Even pushing a button every 108 minutes was beyond him; his inattention caused the crash of Flight 815.

In spite of constant failure, he was unique. A miracle. Immune to the most severe effects of electromagnetism, he traveled freely in time, in any direction. He was the only person in over two thousand years to descend to the Cave of Light and survive. It was he who rendered the Smoke Monster mortal and frail, susceptible to Kate’s bullet and Jack’s final push.

But his greatest accomplishments were achieved in that fifth episode of the fourth season, when the greatest secret of LOST was revealed uniquely, miraculously, by the story’s most expressive character: Desmond David Hume.

A Higher Calling

Desmond Hume had the most diverse background of any of the major characters of LOST, but his life was founded on some of the most predictable patterns as well. Most of his life was spent rudderless, relying entirely on the caprices of those around him to provide the wind to fill his sails and determine his life’s course. Although he was dependent on the whim of strangers, he would not commit, even to his dearest friend and soul mate.

He met Ruth during the 1980s. Though we don’t know how they met, later events in life give us a solid basis for extrapolating a reasonable guess as to circumstance. She was probably performing a function beyond Desmond’s skill level and far outside his normal range of interests. The most obvious possibility is set design. Perhaps she was painting a bridge three metres across that would seem twenty metres wide on stage, explaining her creation to the admiring Scotsman. “Even you could do it,” she might have said. Weeks later Desmond would be painting his own bridges, building his own platforms, designing entire scenes.

The beginning of their relationship would have been innocuous enough. Probably Desmond would have had no understanding of the direction they were headed. If he knew, he would have ended things sooner than he did. He was a free spirit. Even though he loved Ruth he could never commit his life to her, or to anyone else.

“Okay, yes, I was scared about the wedding, so I had a few pints too many… I asked am I doing the right thing, and that’s the last thing I remember.”

He couldn’t commit to Ruth. His ignorance of the responsibilities of life proved to be a blessing in his next vocation, though; if he had known of the rigours and requirements of monkhood, he never would have accepted Brother Campbell’s hand.

“And when I woke up, I was lying on my back in the street, and I dunno how I got there and, there was this man standing over me, Ruth. And he reached out his hand and he said to me, can I help you, brother? And the first thing I noticed was the rope tied round his waist, and I looked at him and I knew, I knew, I was supposed to go with him… I was supposed to leave everything that mattered behind, sacrifice all of it, for a greater calling.”

He had no idea of the life he was pursuing. “We dated for six years,” Ruth told him, “and the closest you ever came to a religious experience was Celtic winning the cup.” He endured the brief test of postulancy, somehow remembering not to speak a single word for the several weeks of the examination period, and became a novice monk. But the Abbot knew he was not called to religious life, even before Desmond sampled an entire bottle of Moriah Vineyards red one evening.

DESMOND: Are you firing me?

BR CAMPBELL: I am indeed.

DESMOND: You can’t do that, I heard the call.

BR CAMPBELL: I’m sure you did hear the call, but the abbey clearly isn’t where you were meant to end up. I have little doubt that God has different plans than you being a monk, Desmond. Bigger plans…

We might have taken Brother Campbell’s words as the reassuring but ultimately meaningless parting words of a former employer, except for one small photograph on the Abbot’s desk.

Eloise Hawking may or may not have been related to Brother Campbell, but she was surely a significant donor to the monastery. She had no interest in the monastery per se, however she was most interested in the impressionable man who would briefly claim a cell in its dormitory.

The issue for Eloise was Charles Widmore’s penchant for high-end wine and liquor. Moriah Vineyards was the most expensive Scottish red wine, and Charles ordered several cases at a time. Eloise knew Charles sometimes dispatched Penny to pick up a few cases, and that was the nexus of the problem. Desmond could not be allowed to meet Penny.

Perhaps Brother Campbell was delinquent in notifying Eloise of the monastery’s most recent postulant. Perhaps she didn’t make the instructions clear enough to the good Abbot’s ecclesial mind. Or possibly it was an accidental result of miscalculation. Whatever the genesis, the result was not in accord with Eloise’s plans: on the morning of his first day as an ex-monk, Desmond met Penelope Widmore.

A Tear in the Fabric of Time

Desmond’s character and suitability for a sexual relationship with Penny were of concern to neither Eloise Hawking nor Charles Widmore. He might have been the perfect man for Penny, or he may have been the type of man who would use her, or ruin her life. None of that mattered to Eloise, and by force of her unopposable character, none of it could matter to Charles Widmore, either.

That Desmond could not be allowed anywhere near Penny was not due to any defect of character, but entirely the result of his necessary vocation. He had to go to the Island, there to push a button every 108 minutes. So Faraday’s journal said, so it had to be. Widmore took extreme measures to prevent Desmond from involving himself with his daughter.

WIDMORE: You know anything about whiskey?

DESMOND: No, I’m afraid not, sir.

WIDMORE: This is a 60 year MacCutcheon, named after Anderson MacCutcheon, esteemed Admiral from the Royal Navy…. Admiral MacCutcheon was a great man, Hume. This was his crowning achievement.

[Widmore pours some into one glass.]

WIDMORE: This swallow is worth more than you could make in a month. [he drinks it down] To share it with you would be a waste, and a disgrace to the great man who made it — because you, Hume, will never be a great man.

DESMOND: Mr. Widmore, I know I’m not…

WIDMORE: What you’re not, is worthy of drinking my whiskey. How could you ever be worthy of my daughter?

Eloise and Widmore’s efforts paid off. Combined with Desmond’s innate fear of commitment, Widmore’s psychological slap in the face and Eloise’s insistence that he was destined not to marry Penny all conspired to force Desmond to reject Penny’s love. “It’s all happening too soon — you moving in. Your painting rooms; your changing things…. Why would you leave your flat, your expensive flat… I can’t look after you. I haven’t got a job…. I can’t even afford five quid for a bloody photograph. You deserve someone better.”

Desmond’s aversion to responsibility was real, but it is a common characteristic of those of us afflicted with the Y chromosome. Many of us overcome youthful stupidities; my wife and I will celebrate 18 years of marriage and 30 years of friendship this month. I was a much worse case than Desmond, and in many ways I still am. But the point I wish to make here is that settling down into a lifelong commitment is something that even the flightiest among humankind can achieve, and Desmond would have been not at all unique in turning his life around in this manner.

Whether Desmond was eternally destined to spend three years entering the same six integers into a computer every 108 minutes is open to debate. We can deliberate the failures and successes of his early life. We might even argue over the necessity of his actions at the Heart of the Island. But there is one matter to which I believe all must surrender any objection: Desmond Hume and Penelope Widmore were destined to spend their lives together.

This is no small matter. In fact, it is upon this relationship that LOST concentrated the full force of its dramatic energies.

Eloise and Widmore’s actions to separate Desmond from Penny constituted a tear in the very fabric of time. They believed physical presence and action in designated locations of spacetime to have greater influence on events than the connections between people. In this false belief they erred. Neither space nor time, nor even the worst forms of psychological coercion and abuse, could prevent the inevitable union of Penny with her beloved. By attempting to pull Desmond away from Penny they were actually weakening the temporal fabric they so strenuously endeavoured to protect.

The Constancy of Time

“You are uniquely and miraculously special.”

Faraday’s words to Desmond in 2004 had their origin in Desmond’s London flat in 1996. It was there, falling off a ladder while painting, in less than a split second, that Desmond traveled forward in time eight years.

I might have begun this section by stating that in late 2004 Desmond turned the key in the Swan Station reset box and this resetting of time was responsible for his strange spacetime epiphany in 1996. But this would be tantamount to saying the past can be changed, a statement very much in opposition to the prime rule of time travel: Whatever happened, happened.

That Desmond was the single exception, that he was able to work around this rule, should not be taken as licence for those of us endeavouring to understand to take illegal shortcuts in our pursuit of truth. We do not share Desmond’s unique time travel abilities. In the end, who is to say that a fall from a ladder might be any less capable of inducing accelerated travel through time than the turning of a failsafe key at an electromagnetic research station? We are perfectly within the acceptable bounds of analysis to claim that Desmond’s time travel adventures began in London in 1996 and not on an island somewhere in the Pacific in 2004.

Desmond was not able to control the flashes from one spacetime to another, but he did travel freely, in directions that we would understand as forward and backward travel in time. He predicted events, but not accurately. “I remember this night. [he sees a TV showing a soccer game] Graybridge come back from 2 goals down in the final 2 minutes and win this game. It’s a bloody miracle. And after they win, Jimmy Lennon’s going to come through that door and hit the bartender right in the head with a cricket bat because he owes him money.” Desmond remembered the incident correctly–but he was exactly 24 hours off; Jimmy Lennon didn’t come into the pub until the day after Desmond’s prediction, but he did exactly as Desmond predicted.

Course Correction

Eloise wore an ouroboros pin during her lecture on the rules of time. Seeing the brooch made me deeply aware of what we lost on May 23, 2010. Such care was taken in enriching every scene with symbols and meaningful, multi-faceted images and dialogue. LOST had unparalleled depth and significance–to the extent that even months later we are endeavouring to unravel its meaning. LOST is a magnificent gift we can treasure, but there is a certain sadness in knowing we have only six years to examine.

According to Lostpedia, “Ancient civilizations used The Ouroboros as a symbol of Recurrence. Typically the symbol consists of a snake’s body forming a circle with the head swallowing the tail.” We know of several instances of time loops in LOST. I have written extensively about the compass, for example, endlessly exchanged between Locke and Richard in a continual loop between 1954 and 2007 (see http://pearsonmoore-gets-lost.com/TheGoodGuys.aspx, under the header “Compass”).

Many such time loops were created, and in fact, the entire edifice of the series was built on the predictability and periodicity of temporal event and human behaviour. “They come, they fight, they destroy, they corrupt. It always ends the same.” The Smoke Monster could never lose, because he knew the rules, and predictability, immortality, and imperviousness to any instrument of death meant he would always be several steps ahead of any challenger. The fabric of the universe was warped in his favour.

Changing a single event in the past was possible. Because Desmond floated freely between past and future, he knew the course of events, and he could take action to prevent undesired outcomes. But that was not enough, because the universe tended to correct course.

MS. HAWKING: That man over there is wearing red shoes.

DESMOND: So, what then?

MS. HAWKING: Just thought it was a bold fashion choice worth noting.

….

[Suddenly, there is a loud crash behind the bench Ms. Hawking and Desmond have been sitting on. Some scaffolding has fallen and killed the man with red shoes.]

DESMOND: Oh, my God. You knew that was going to happen, didn’t you?

MS. HAWKING: [nods]

DESMOND: Then why didn’t you stop it? Why didn’t you do anything?

MS. HAWKING: Because it wouldn’t matter. Had I warned him about the scaffolding tomorrow he’d be hit by a taxi. If I warned him about the taxi, he’d fall in the shower and break his neck. The universe, unfortunately, has a way of course correcting. That man was supposed to die. That was his path just as it’s your path to go to the island. You don’t do it because you choose to, Desmond. You do it because you’re supposed to.

Charlie Pace had to die on the Island. He had been destined to die by electrocution in a lightning storm, but Desmond foresaw his death and used a golf club and wreckage wire as a lightning rod, saving Charlie’s life. The universe course-corrected by planning Charlie’s death by flying arrow through the neck, but Desmond saw the future, and again took steps to prevent fate from taking his friend.

Finally, after preventing the musician’s death by drowning, Desmond told Charlie the truth: Charlie was going to die.

An objective observer might conclude that Charlie’s presence in the Looking Glass Station, and his crucial three-word warning (“Not Penny’s Boat”) to Desmond altered the course of time. By delaying Charlie’s death until he made a substantial contribution to everyone on the Island, any “course correction” would be partial at best. Therefore, Desmond successfully broke the rules of time travel.

Many sound theories have been based on this premise, and I have to believe there is merit to such a claim. Most importantly, Charlie’s warning, and his death, served to enhance Locke’s position, proving his actions–even his murder of Naomi–to have been more than warranted. Many on the Island would die because of the freighter mercenaries’ unholy project, and Charlie’s warning undoubtedly saved many lives.

There were obvious short-term effects, such as Hurley’s decision to follow Locke so that Charlie’s death would not have been in vain. The credibility boost that Locke received may have had long-term effects, as well. It is possible the Charlie’s support of Locke’s position may have helped sway Jack during his three years off the Island, possibly accelerating his movement toward life as a Man of Faith.

Sound arguments can be made against this theory, but I do not wish to debate them here. Whether Desmond’s actions to save Charlie constituted a violation of the rules of time travel, he certainly achieved something of note to the story in saving Charlie’s life three times, and in being present to receive Charlie’s warning. I believe notable importance attaches to this fact, since part of Eloise’s rationale for forcing Desmond to the Island was to ensure three years of code entry as “the only truly great thing” Desmond would ever accomplish. I disagree. I believe saving Charlie and at least three other acts were of greater moment than entering the integers every 108 minutes.

Physical Endurance

After rejecting Penny, Desmond walked by a Royal Scots Regiment recruiting office. Volunteering may have been the result of long planning and research, but this seems unlikely. Regardless of the time and care he may have taken in reaching a decision about military service, he was psychologically and physically unprepared for the rigours of life in the Royal Scots. Desmond had a strange knack for choosing vocations for which he was particularly ill-suited at the time.

But fate conspired against Desmond in ways he never could have prepared for. Even if he had been in top psychological and physical shape, he could never have steeled himself for the disorienting effects of suddenly traveling several years into the future.

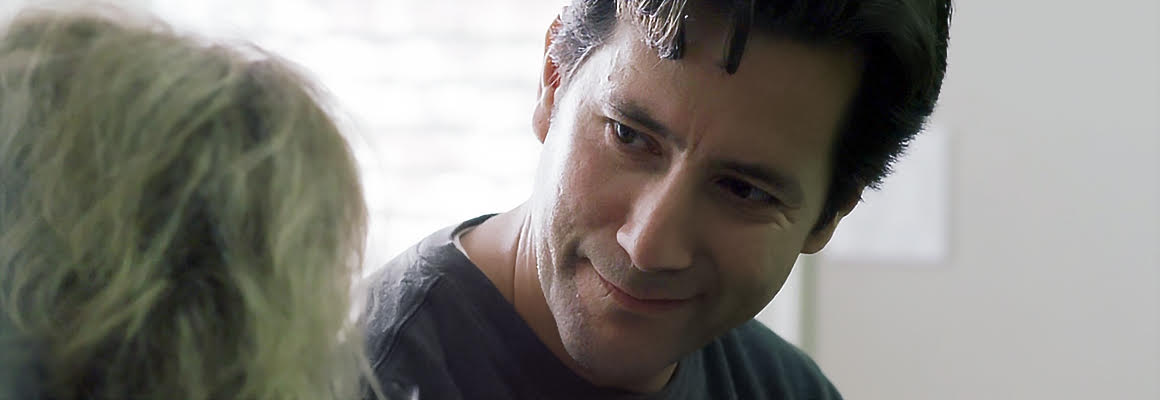

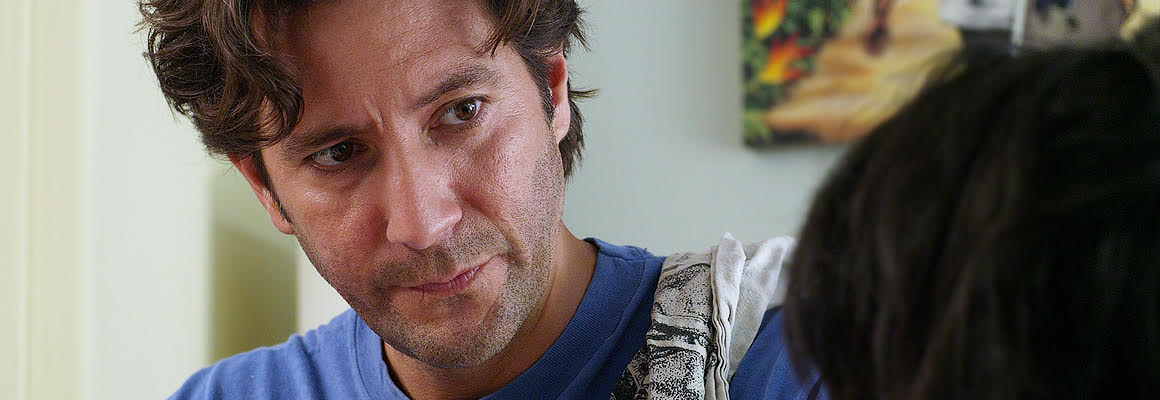

He faced the deepest challenge of his life during the Christmas of 2004. He had no anchor in time, no Constant to orient him, and the result was physical trauma. The violent effects of sudden, involuntary time travel were literally ripping him apart inside, tearing him out of the fabric of time.

As his 1996 self struggled in the frightening and utterly disorienting environment of an ocean freighter in the Pacific Ocean in 2004, Desmond was in deep trouble. His nose had started to bleed. “When it happens again, Desmond, I need you to get on a train,” Daniel Faraday told him. “Get on a train and go to Oxford. Oxford University. Queens College Physics Department.” Daniel Faraday at that time was Professor Daniel Faraday, and he was conducting experiments in time travel. The younger Daniel Faraday was the only person in the world who could help Desmond.

Professor Faraday explained to Desmond his need for an anchor, or Constant. An anchor was “Something familiar in both times. All this, see this is all variables, it’s random, it’s chaotic. Every equation needs stability, something known. It’s called a constant. Desmond, you have no constant. When you go to the future, nothing there is familiar. So if you want to stop this, then you need to find something there … something that you really, really care about … that also exists back here, in 1996.”

Death in Its Many Forms

Minkowski was in the late stages of time travel-induced internal haemorrhaging. Bleeding from eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, he would be dead in hours or minutes, and no medication or surgical procedure could prevent his demise. This would be Desmond’s fate as well, if he did not find a Constant.

In 2008 we didn’t yet know the full ramifications of living life without a Constant. In the context of Minkowski’s and Desmond’s time travel it seemed the requirement of a Constant was a special case, that the majority of mortals who do not experience the frightening disorientations of time travel will never need to invest ourselves in “something that you really, really care about”.

At the end of Season Six we learned one of the possible consequences of not vesting in something important outside oneself.

HURLEY: Hey, you around? Michael?

[Michael steps out of the jungle.]

HURLEY: You’re stuck on the Island aren’t you?

MICHAEL: [nodding] ‘Cause of what I did.

HURLEY: And…there’re others out here like you, aren’t there? That’s what the whispers are?

MICHAEL: Yeah. We’re the ones who can’t move on.

Michael committed horrendous deeds of murder and deception, but his acts did not compare to Sayid’s multiple murders or the atrocities Ben carried out. Yet Ben was allowed into the sideways purgatory, and Sayid was allowed to “move on” in the Church of the Holy Lamp Post at the end of the story. Michael was left behind not because of what he did, but because of what he did not do. He did not forge an enduring relationship with his wife, and their marriage ended in divorce. He did not develop a strong relationship with his son, nor with anyone else, for that matter. Friends he might have retained he instead alienated by killing Ana Lucia and Libby, and by deceiving those he didn’t hurt directly.

Michael had no Constant. It was this fact that prevented him from “moving on”.

The importance of a Constant–something to which a person makes an enduring commitment that stands every test of time–is of paramount importance in the world of LOST. Without a Constant, one cannot receive a place in the pews of Our Lady of the Foucault Pendulum. Establishing a life-long relationship is the primary message of LOST, as explained here:

http://pearsonmoore-gets-lost.com/ConfluenceofRedemption.aspx

Those whose consciousnesses travel through time without a Constant will experience disorientation, internal bleeding, time seizures, and death. Those who die without a Constant will experience only whispers and shadows–the endless sadness of realising what might have been, the eternal emptiness of spiritual isolation.

Rectifying History

Eloise Hawking and Charles Widmore were not objective “time cops” selflessly devoting themselves to the maintenance of the universe’s internal clock. Eloise’s objective was to make amends for killing her own son. Widmore’s plan was to seize control of the Island. When Eloise told Desmond that his destiny was not with Penny, she was wrong. She may have been correct that Desmond was destined to enter the Valenzetti coefficients every 108 minutes for three years until the computer was destroyed and he was forced to turn the failsafe key, but she was incorrect again in stating that “pushing that button is the only truly great thing that you will ever do.”

Desmond’s trans-spacetime experiences of Penny had relevance to him because of the constancy of their relationship. Regardless of any of the particulars of the reality around them, they were destined to recognise in each other something essential to their being. In the sideways reality or on the Island, they found the completion of themselves in each other.

In the world of LOST, nothing is more important than the establishment of a personal Constant. A Constant is necessary to a life well lived, and it is necessary to those who wish to “move on” from this life to the next (see http://pearsonmoore-gets-lost.com/ConfluenceofRedemption.aspx). Without a Constant, one is destined to spend eternity with the whispers and regrets of a life devoid of meaning.

In contacting Penny from the freighter during Christmas, 2004, Desmond was not changing history. He was rectifying the time error that Eloise had attempted to perpetrate. Desmond needed Penny for his own survival, but he was accomplishing something much more important, for he was to become the central figure in the Island’s most important event, and our story’s final chapter.

The Triumph of Odysseus

Menelaus, the most powerful man in Mycenae, summoned the King of Ithaca, Odysseus, to fight a war in a foreign land to restore property rightfully his. Three thousand years ago the great adventure began with the launching of a thousand ships to recover from Troy the woman whose beauty has never been equaled. Our modern-day Menelaus, the most powerful man in England, summoned ocean-faring Odysseus to fight a war in a foreign land, to restore property he claimed as his own, a land whose power has never been equaled. Three years ago, in 2007, this final battle of the great war began with the launching of a single submarine. For the magnificence of our great Odysseus was such that he alone could usurp the power of the gods, turning their immortality to dust.

The Odyssey is the world’s greatest adventure story, and Odysseus the world’s greatest hero. Son of a god, Odysseus inherited deep masculinity and strength of purpose. He carried himself in the manner of all men aware of their abiding dignity; in Homer’s words, he was “in bearing, like a god.” The great king and hero of the Trojan War took a torturous ten years to return to Ithaca, facing every manner of physical test of his crew and himself.

But we know Odysseus not for his great physical strength, rare masculine beauty, or dignified bearing. We know Odysseus as the resourceful fighter, the cunning leader, the man who, by guile and force of character, finds a way out from seemingly impossible situations. During the war, he thought up and fashioned the Trojan Horse. To defeat the Sirens, Odysseus had his men poured wax in their ears so they could not be lured by the seductive devils’ irresistible song. Captured by the giant Cyclops, facing certain death at the hands of the one-eyed cannibal, Odysseus plied the monster with wine, waited until he fell asleep, then burned out his single eye. After ten long years, he returned to his Penelope.

Desmond endured physical challenges of space and time in his quest to return to his Penelope–to his Penny. Shipwrecked, like Odysseus, spending long years on an island, like Odysseus, he never gave up hope of finding her. Most of all, like Odysseus, we know Desmond not for any physical ability, not even for the rare capacity to resist the terrible physical effects of unearthly magnetic force, but rather for his strength of character, for strength of spirit. Desmond deserved Penny not for any physical prowess or superhuman ability, but for entirely human reasons: for faith in their sharing, for hope of finding her, for love of her as soul mate, friend, wife. Most of all, for never giving up, for applying every resource he could muster to find her and keep her.

Desmond–the Island’s Odysseus–is made hero because of his humanity, because of the choices he made, because of his relentless drive to share love with Penny. The awful force of the magnetic chamber–sufficient to kill ordinary mortals–was no challenge to our Odysseus. His easy triumph over the normal constraints of the physical world, and in fact his triumph over the very fabric of space and time, was not the message of the final battle. The lesson driven home is that Desmond’s unrelenting focus on Penny allowed him to achieve in the spiritual realm feats that far outshine even the superhuman abilities he demonstrated with so little effort in the magnetic chamber.

Desmond’s humanity is more important, and more powerful, than the greatest of superhuman abilities. This is an important revelation, and quite possible the single most critical truth of series. Desmond is the physical embodiment of the great truth of LOST:

Humanity is more important, more enduring, and stronger than anything in the physical world.

Odysseus’ physical body expired thirty centuries ago. But his spirit lives on, and can never be vanquished. On the Island there is nomos (law) and physis (nature). The forces at play are stronger than anything known in the physical world. But the force above all forces is the only one that is truly irresistible and unstoppable: Pneuma (spirit). Desmond’s success was inevitable, not because of Jacob’s “progress”, but because this is how we are made. This is who we are, as human beings, as those aware of innate, abiding dignity, carrying ourselves in calm possession of every faculty of mind and body, in bearing, like a god.

Our Necessity, Our Triumph

Favoured of the gods, Odysseus returned home to his Penelope, but only after enduring trials, torments, and tribulations. He was of all the characters of LOST the most expressive, the most adaptable, the most willing. He performed his mighty deeds and exited quietly without acknowledgment or fanfare. He saved Charlie, and by doing so enabled the musician to perform the single greatest act of his life. He defied Eloise and Widmore and restored his relationship with the only woman in the world who truly mattered. He moved a stone that no other could touch, a simple act that turned an immortal force of nature into a fragile old man, and allowed the great Man of Faith to restore peace to the Island and equilibrium to the world.

Fair Odysseus, in bearing like a god, was as human as any among us. He was our triumph, our necessity, for in every age women and men of character and will quietly perform great feats that no others dare. In a story of magnificent men who lead legions and armies, of great warriors who win against crushing odds, we remember first the quiet one. We read of wise Agamemnon, strong Ajax, good Diomedes, cunning Menelaus, kind Patroclus, incomparable Achilles. Their strategies and speeches and battles fill the pages, testament to heroism, record of brotherhood, witness to destiny. But the greatest of these is fair and strong, quiet and sure, testament of humanity, witness to civility. The greatest of these, the one we remember in our dreams, carry in our hearts, proclaim in our words, with wisdom surpassing Agamemnon, strength beyond Ajax, kindness above Patroclus, is the one beloved of Athena, beloved of Penelope: the quiet one, the good and fair Odysseus, the Scotsman, Desmond David Hume.

PM

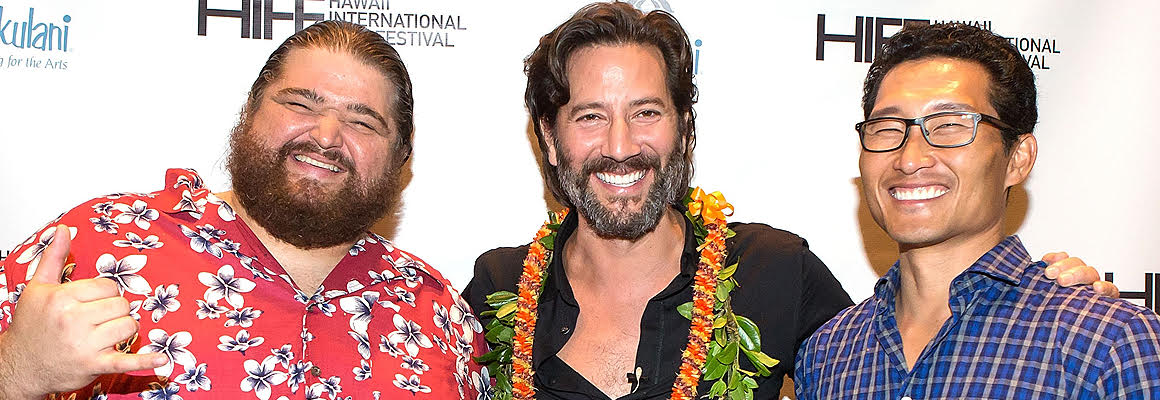

![[1198657408]a MacGyver](https://www.cusickgallery.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/1198657408a-MacGyver-e1627604023448-1160x400.jpg)

Awaken Film

Awaken Film Henry Ian Cusick – Facebook

Henry Ian Cusick – Facebook Henry Ian Cusick – Vimeo

Henry Ian Cusick – Vimeo Henry Ian Cusick – YouTube

Henry Ian Cusick – YouTube Henry Ian Cusick Official Site

Henry Ian Cusick Official Site Henry Ian Cusick SoundCloud

Henry Ian Cusick SoundCloud Henry Joe Productions

Henry Joe Productions Birthday Edition

Birthday Edition 1 Million Followers

1 Million Followers 10.0 Earthquake

10.0 Earthquake After the Rain

After the Rain Awaken

Awaken Carla

Carla Chimera

Chimera Darwin's Darkest Hour

Darwin's Darkest Hour Dead Like Me:Life After Death

Dead Like Me:Life After Death dress (directoral debut)

dress (directoral debut) Fluxx

Fluxx Frank vs. God

Frank vs. God Hae Hawai'i

Hae Hawai'i Half Light

Half Light Hitman

Hitman Jamojaya

Jamojaya Just Let Go

Just Let Go Not Another Happy Ending

Not Another Happy Ending Pali Road

Pali Road Perfect Romance – Lifetime

Perfect Romance – Lifetime Rememory

Rememory The Girl on the Train

The Girl on the Train The Gospel of John

The Gospel of John The Wind & The Reckoning

The Wind & The Reckoning Visible

Visible Theatre Gallery

Theatre Gallery Adventure Inc.

Adventure Inc. Casualty

Casualty Happiness

Happiness Midsomer Murders

Midsomer Murders Murder Rooms

Murder Rooms Taggart

Taggart The Book Group

The Book Group Two Thousand Acres of Sky

Two Thousand Acres of Sky Waking the Dead

Waking the Dead 24 – Fox

24 – Fox 911: Lone Star

911: Lone Star Big Sky – ABC

Big Sky – ABC Body of Proof – ABC

Body of Proof – ABC CSI: Las Vegas – CBS

CSI: Las Vegas – CBS Fringe – Fox

Fringe – Fox Hawaii Five-O – CBS

Hawaii Five-O – CBS Inhumans – ABC

Inhumans – ABC Law and Order: SVU – NBC

Law and Order: SVU – NBC Lost – ABC

Lost – ABC NCIS: Hawai'i – CBS

NCIS: Hawai'i – CBS Scandal – ABC

Scandal – ABC The 100 – The CW

The 100 – The CW The Mentalist – CBS

The Mentalist – CBS The Passage – Fox

The Passage – Fox HTY – The HI Way Series

HTY – The HI Way Series JamBios

JamBios Nestor Carbonell Central

Nestor Carbonell Central Petition – Carlton Cuse – Please Make A Show For Team Caliente (Henry Ian Cusick and Nestor Carbonell)

Petition – Carlton Cuse – Please Make A Show For Team Caliente (Henry Ian Cusick and Nestor Carbonell) Cusick On Screen – Instagram

Cusick On Screen – Instagram CusickChick's Tumblr

CusickChick's Tumblr Henry Ian Cusick – IMDb

Henry Ian Cusick – IMDb Shannon's Tumblr

Shannon's Tumblr Yatanis Tumblr

Yatanis Tumblr CusickGallery Facebook

CusickGallery Facebook CusickGallery Instagram

CusickGallery Instagram CusickGallery Pinterest

CusickGallery Pinterest CusickGallery Tumblr

CusickGallery Tumblr CusickGallery Twitter

CusickGallery Twitter CusickGallery YouTube

CusickGallery YouTube Des & Pen Fanpop spot

Des & Pen Fanpop spot Desmond Hume Fanpop spot

Desmond Hume Fanpop spot FanForum – Henry Ian Cusick

FanForum – Henry Ian Cusick FanForum – Marcus Kane

FanForum – Marcus Kane HIC Fanpop spot

HIC Fanpop spot Kane & Abby Fanpop site

Kane & Abby Fanpop site Lost Screencaps site

Lost Screencaps site